Financial Crimes OSINT Tools: Shell Companies

An Investigator’s Guide

Global Endeavor Inc. Avionica International & Associates Inc. 25CC ST74B LLC. Shell companies are a fixture of global illicit finance, tools of rapacious despots, scheming mafiosi, and cheating spouses. They are implicated in almost every high-profile international crime, giving cover to sanctions busters, tax evaders, and war criminals.

Though even law enforcement struggles to identify the owners of many shell companies, the tools and data necessary to identify such companies are publicly available for use by citizen journalists, open-source investigators, and compliance analysts. In this article, I aim to empower researchers by a) describing shell companies and their use, b) showing the process by which they are created, and c) providing a list of common characteristics they share.

What are shell companies, and why do they exist?

Ordinarily, we think of companies as organizations that produce goods or services of some kind — for example, Apple Inc. produces electronics, and Walmart Inc. operates a chain of retail stores. In reality, companies are merely legal entities. Those entities can be used for business activities, or they can hold property, purchase real estate, and own bank accounts. A shell company is a type of company that by definition does not engage in normal business operations — in fact, shell companies often do not physically exist at all, other than a few paper forms.

What, then, is the purpose of having a shell company? There are many reasons; some are benign, others not. Examples of licit uses include holding assets in a location with reduced tax liability or avoiding the legal risks of incorporating in a politically-unstable jurisdiction. Shell companies can also offer legitimate anonymity: opponents to recent transparency reforms have argued that high-profile or wealthy individuals should be allowed to purchase property through anonymous shell companies to maintain their privacy. If a rich family’s address is accessible in property records, they argue, they may be targeted by kidnappers or thieves.

Criminals love shell companies for some of the same reasons as non-criminals, particularly their promise of anonymity. Illicit arms traders, corrupt politicians, sanctions busters, and other crooks use shell companies to put distance between themselves and their crimes — if an investigator “follows the money,” they might find that the trail stops with an anonymous LLC in Nevis, and who’s to say whether the owner of that company isn’t Bashar al-Assad or Viktor Bout? It is difficult for even law enforcement to pierce the veil of secrecy around shell companies, especially if they are domiciled in uncoöperative jurisdictions.

How are shell companies created, and what makes them anonymous?

To understand what makes shell companies so anonymous, it’s important to learn the basics of how they are made.

Let’s say that I want to set up a shell company to receive a bribe. I don’t want to go down to city hall and put my name on a bunch of documents, or there would be a public paper trail connecting me to the crime. Instead, I go to my lawyer or my Swiss banker, and I let them know that I need to do some discreet business. They, in turn, reach out to a “corporate service provider” (CSP), a firm that registers corporations in bulk and sells them to intermediaries or end customers. Well known CSPs include Mossack Fonseca, the now-defunct Panamanian subject of the Panama Papers investigation, and Appleby, the Bermudian subject of the Paradise Papers investigation. A quick Google search for “offshore company formation” or “offshore incorporation services” returns a long list of such providers, some of which blatantly market their product as cheap, fast, and secret. Let’s say that my lawyer reaches out to this actual CSP in the Seychelles:*

The CSP is happy to serve me for a fee. I simply need to provide certain documentation to fulfill Know Your Customer (KYC) regulations — this firm requires that I provide a copy of my passport or ID, proof of address, and possibly a bank reference, though they also stress that the names of company officers and other identifying data will not be made public.

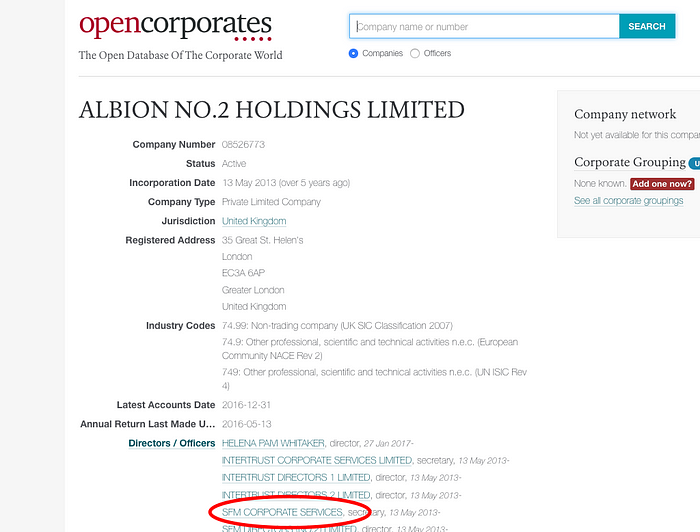

At this point, I could provide that information and the company would be owned by me. According to the government and on public records, however, the company officer would be the CSP as a “registered agent.” In the actual corporate registration below, you can see that this exact CSP is included as an officer of Albion Holdings, though Albion has also provided additional named directors. I could choose not to do so, in which case only the CSP name and possibly the name of a CSP-provided “nominee officer” would be listed under “Directors/Officers.”

I could then set up a bank account in the company’s name and the bribe could be paid into that account. I’d have the money, and anyone looking at the transaction would see that the payee paid a random company directed by the CSP, not me. I could then make a false invoice saying that I’d provided consulting services or some widgets to the shell company, and charge them the amount of the bribe. Voila! They pay me, and I can buy a shiny new Porsche.**

Common attributes of shell companies

Here are some “red flags” that can help to find suspicious shell companies. Please note that none of these are dead giveaways on their own, and that several of the flags would need to be present before a company can be confidently classified as a shell corporation.

Offshore/Tax Haven jurisdictions

Certain countries/states/territories are notorious for hosting shell companies — the British Virgin Islands, Panama, Hong Kong, Seychelles, Mauritius, Nevis, Belize, Bahamas, Gibraltar, Isle of Man/Jersey/Channel Islands, the UK, Delaware, Samoa, and Cyprus are among the best known.

Each has its specialty: “At the top of the food chain — as far as the western world goes, anyway — are places such as London, Switzerland and New York. These apex predators are surrounded by clouds of pilot fish that snap up the scraps: places such as Monaco, Jersey and the Cayman Islands. These smaller centres all play different aspects of the offshore game: Jersey specialises in trusts, the BVI in incorporation, Liechtenstein in foundations. They also differ in their tolerance for criminality. Among the British territories: Gibraltar is dodgier than Guernsey, but cleaner than Anguilla. And they serve different geographical regions: Mauritius for Africa and India; Cyprus for the former Soviet Union; the Bahamas for the US” (Source).

It’s worth noting that not all companies registered in such places are bad, and not all bad companies are registered in those places. Often bad press has motivated “offshore” jurisdictions to clean up their acts and become extra compliant. Nevertheless, many suspicious companies are domiciled in those countries, and in cases where the beneficiary has little connection to the incorporation country, suspicion is raised.

Registered agent addresses

Often the address provided by a shell company is that of the CSP or is an address used by the CSP in documents for numerous corporations. Throw the address into Google and see what comes up: is the address shared by numerous other companies? Does it belong to a business services company (like an accounting firm or consultancy) or CSP? Also check the address in Google Street View: does it make sense for the company to be based in that location? If they’re a multi-million dollar chemical importer, why are they based in a suburban home?

Buzzfeed recently published an article tracing a network of 100+ companies with a shared nominee director and ties to numerous shady characters. All were based out of the same 4 addresses in London:

Doesn’t look too convincing.

Bland, meaningless names

These could belong to shelf companies***— when CSPs register batches of companies for no particular client, they choose company names that could appeal to a wide range of customers. Think AAA Holdings Pte. or Lotus Star LLC. It could also be a sign of a customer wanting to obscure the company’s line of business. Of course, a vague name alone is not a sure-fire sign, but it’s worth considering.

No web presence

These days, it makes sense for almost every business to have a web presence, even if they aren’t dealing directly with end customers. This could be an Alibaba shop, a Yellow Pages listing, a proprietary website, or anything that states the company’s line of business. A lack of effort to promote itself suggests that the company may not want to be known.

Bank account and company located in different jurisdictions

Beneficial owners typically want to keep bank accounts nearby so they’re easier to use, or they may start accounts in places with banking secrecy like Switzerland or Lichtenstein. As a result, shell companies are often domiciled far from associated accounts. For example, if I see that Golden Honor SA in Panama is banking in Germany, I would suspect that the owner is in Germany and that the company is a shell.

If you have access to the company’s transaction history, here are some extra red flags:

Transactions have no stated purpose (in wire notes)

Pretty self-explanatory. Invoice numbers in the wire notes don’t mitigate suspicion unless the corresponding invoice is available for review.

Large, unexplained payments/payments to an unusually high number of beneficiaries

Broadly, any unusual/inexplicable money movement requires extra scrutiny.

In Conclusion

Although finding a shell company does not always mean a) that the shell company is suspicious or b) that the resources to identify any suspicious activity by the company are available online, corporate registries and other open data sources have aided numerous important investigations like these.

*There is nothing especially suspicious or shady about this particular firm, I just found it in a Google search as an example.

**Let’s say that the IRS or FBI or some other law enforcement group takes interest in the payment and want to investigate. They contact their counterparts in the Seychellois government, who show up with a subpoena at the door of my CSP. My name is in the CSP’s files as the owner of the company, and I get caught. How could I prevent my name from being revealed, even in that worst-case scenario?

That’s where the dark arts of incorporation come in.

One trick is to use bearer shares. A bearer share is a physical document that serves as the deed to a business, and anyone who physically possess it technically owns the business. If I hand the bearer share to the nominee director at the CSP, who then puts it into their office safe, they become the owner of the company. I may have an understanding with the nominee that I am the real beneficiary of the business and that they must obtain my permission to conduct any business, but when the police show up to take the private ownership data, the nominee can truthfully state that the company is theirs. For this reason, bearer shares have been outlawed in many jurisdictions.

I could also create a shell company to own a second shell company, thus creating additional layers of secrecy and making it more difficult for law enforcement to trace me. In an attempt to prevent this, many governments require that the identity of the “beneficial owner” — the individual actually benefiting from the company — be disclosed. In response, some CSPs have actually offered nominee beneficial owner services. This is clearly and completely illegal, and it’s a service that is only offered under the table by unscrupulous firms. One of the revelations of the Panama Papers was that Mossack Fonseca provided nominee beneficial owners, paying the ex-father-in-law of one of the firm’s principals to sign documents as the beneficial owner of numerous companies. In addition to being criminal, the service was expensive: one woman reportedly paid $60,000 to use a nominee beneficial owner for 3 years.

In addition to all this, there are many firms that simply don’t comply with KYC law. They will not require a passport or other information in return for a higher fee. For their book Global Shell Games, Drs. Mike Findley, Daniel Nielson, and Jason Sharman conducted a massive study of CSPs worldwide in which they contacted CSPs asking to create shell companies while hinting that they had malign intent (e.g. they wanted to find terrorism) or refusing to provide documentation. They found that “nearly half (48 percent) of all replies received did not ask for proper identification, and 22 percent did not ask for any photo identity documents at all to form a shell company.” (The US and other “developed” countries were fearfully bad at complying with due diligence laws, by the way.)

***“Shelf companies” are shell companies that are incorporated by a CSP and placed on a shelf for a time before being sold to an end user. They are valuable because a years-old company looks more trustworthy than one that was incorporated yesterday. They are also sometimes marketed as “vintage companies.” Here are some shelf companies offered by our CSP: